The way objects relate to each other and extend to represent things in an application is called inheritance, and it’s necessary for building large and complex applications.

The object system that JavaScript implements is a prototype-based, class-free system. Understanding how it works will help you grasp one of the great pillars of JavaScript.

But let’s go step by step.

Why Is Inheritance Important?

Object-oriented programming gained wide acceptance because it offers a useful perspective for designing programs, aiming to make our code portable and reusable.

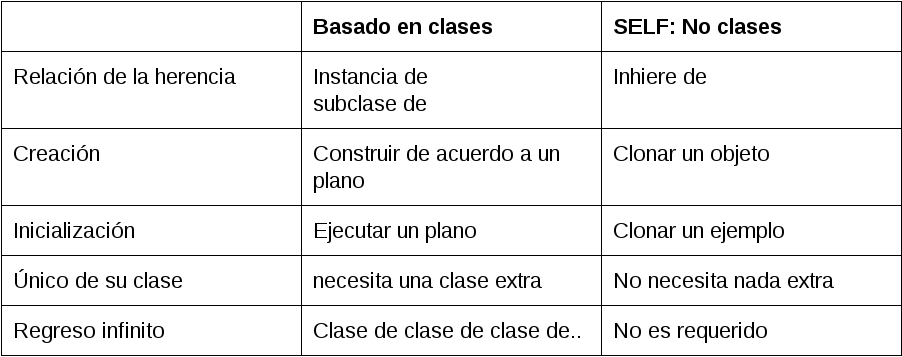

However, not all languages share the same perspective on how objects relate to each other. Different ideas exist about the nature of object-oriented programming.

But if inheritance isn’t applied correctly, it will make our software difficult to modify or scale.

One of the most famous languages that many others were based on was SmallTalk, which implemented class-based inheritance and hierarchies, and many programming languages have been based on it.

But there are also some other ideas out there. Among them, a very important one was proposed by a programming language called SELF, which proposes prototype-based inheritance. Brendan Eich based JavaScript’s implementation on it.

Here you can find the SELF papers — I recommend reading them.

Before looking at it in JavaScript, I’d like to show some ideas that SELF proposes.

SELF: The Power of Simplicity

One of SELF’s goals was to create a simpler relationship between objects. To achieve this, as they say, they “trimmed all the fat,” leaving only objects — no need for classes. To create relationships between them, they used prototypes and cloning.

Two of the most important characteristics are:

- Prototypes: Combining inheritance and instantiation to provide a simpler and more flexible way to link objects.

- Slots: Variables and procedures in a single constructor that doesn’t distinguish between them.

Also, as I mentioned, in SELF there are no classes — just objects that serve as pieces to build other objects by cloning them, or linking them to share information.

In contrast to SmallTalk, where everything is an object and you must instantiate a class to have an object, in SELF everything is also an object, but these objects are linked. If a message is sent to an object and the property isn’t found, the search continues through the linked objects. This is how inheritance is applied.

One of the most interesting aspects is the way it combines inheritance, prototypes, and object creation, eliminating the need for classes

It’s also possible to create new objects from prototypes using a simple operation — clone. This way we can build objects from others, like Lego pieces.

How Is It Implemented in JavaScript?

Since JavaScript is based on SELF, it’s class-free. Therefore, classical inheritance is not implemented. Given the language’s implementation, it uses prototype inheritance, which is more simple, flexible, and powerful.

But this has been one of the least understood things about the language over the years, and there are a few reasons for that:

- When JavaScript was implemented, Netscape required a syntax similar to Java. That’s why we have keywords like new or instanceof in the language, which make people believe you can instantiate classes.

- The term “inheritance” refers to copying, and this doesn’t represent how things work in JavaScript. That’s why authors like Kyle Simpson, author of You Don’t Know JS, clarifies that it should be called OLOO (Objects Linked to Other Objects).

Since many developers don’t understand the inheritance system implemented in JavaScript, they’ve tried to simulate or implement things similar to classical inheritance — but all of these work on top of prototype inheritance.

What Differences Exist?

Classical inheritance: A class is like a blueprint that describes the attributes and methods of the objects to be created. Classes can inherit from other classes (code reuse), creating a hierarchical relationship.

In many languages, this is the only way to create objects. But in a few, objects can be created without needing to instantiate a class (like in JS). So having to instantiate a “class” is itself a pattern called the constructor pattern.

In JavaScript, this pattern is implemented using a function as a constructor, “instantiating” with the new keyword, and using the internal [[prototype]] method to delegate properties and create a hierarchy.

All of this is built on top of prototype inheritance, but it doesn’t have the same power and flexibility, since it falls into all the problems of classical inheritance.

Prototype inheritance: Objects link directly to other objects. They can link to one or several objects.

In JavaScript, we have three correct ways to implement prototype inheritance:

- Concatenation: Properties are copied from one or more objects into a new target object. This is also known as mixins, and since ES2015, there’s a simple way to do it with Object.assign()

- Delegation: If a property is looked up on an object and isn’t found, the search continues in the object linked via

[[prototype]], all the way up to Object.prototype. To control and determine this link between objects, we have Object.create() - Functional: Any function can return objects, taking advantage of closures to have private properties. These are called factory functions, and the returned objects can be extended directly.

In the following posts, I’ll cover each of these inheritance approaches separately.